Module # 3 -- Person

http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/cd3b1449398da3fd1613e517604f3931.pdf http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/f5a84c237f88fc5f5e5a33a90e295b91.pdf http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/0f0eda22149e2be923e980b23a24166e.pdf

http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/cd3b1449398da3fd1613e517604f3931.pdf http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/f5a84c237f88fc5f5e5a33a90e295b91.pdf http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/0f0eda22149e2be923e980b23a24166e.pdf “A lady…who was present on the spot”—phrases like that or similar variations are the main identifiers given to the author of an “account of the siege of Gibraltar”, an excerpt from a diary printed in several British magazines in 1781. Although the magazine excerpts do not identify her by name, the “lady” is Catharine Upton, the wife of a Lieutenant of the 72nd Regiment of Foot (Manchester Royal Volunteers)[1] and an amateur published poet. Upton published this full account of the Siege in London in 1781 after leaving Gibraltar during the naval relief of the city under Vice Admiral George Darby. In 1784, she published “Miscellaneous Pieces”, a volume of her writings. Despite her published works, Upton remains an elusive figure. All information known about her comes from her two works; other information is conjecture or indirect evidence. In this sense, Upton is almost a paradox: even though she left behind two published works in her own voice, she still appears to leave no easily searchable trace. In other words, Catharine Upton, “the Authoress of the Siege of Gibraltar and Governess of the Ladies Academy” is both known and unknown.[2]

Almost no information is known about Upton’s early life, and so here one must turn to historical context and conjecture. It is not known when or where she was born, when she married Lieutenant Upton, or precisely when Upton and her children followed her husband to his post on Gibraltar. One can generalize the circumstances of her marriage and life on Gibraltar before her diary from what is known about military marriage in the 18th century in Britain. In the early- to mid-18th century, more junior officers (including lieutenants) and common soldiers were discouraged from marrying or prohibited altogether.[3] By the late 18th century, the restrictions on marriage in the British army had proved largely ineffective.[4] Officers brought their wives with them on assignment, despite cultural attitudes developing in the 18th century that disparaged army wives and the soldiers who brought them into battle. Still, this tells us nothing concrete about Upton, except that she was part of a thriving tradition of women attached to the British armed forces. Given the societal disfavor to married subaltern officers, it is possible that she married her husband before he was commissioned for the 72nd Regiment.

Her written works, “Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse” and “The siege of Gibraltar, from the twelfth of April to the twenty seventh of May, 1781”, provide most of what is known about Catharine Upton’s life during and after the Siege. Here, one learns that in 1781, she was a wife, mother, and writer living in Gibraltar. She identifies her husband as a “lieutenant of the picquet”, though she also indicates that this is a temporary position he held.[5] Upton does not name him here, but later records indicate that his name was John.[6] She reveals that she is the mother to at least two children, a son Jack and a daughter.[7] She also indicates that the Upton family was moderately well off, employing at least one servant and owning a house in Gibraltar. Finally, Upton reveals that she fled Gibraltar with those children in 1781 after a minor naval relief force reached the city, leaving her husband behind.[8] After reaching London, she determinedly sought a military commission for her son and decided to publish the “Account” from a series of letters she was going to write for her brother.[9] From “Miscellaneous Pieces”, the preface to the piece informs the reader that Upton became the governess of a ladies’ school some time after 1781. She does not mention her husband, but she does say that she writes to support her children. This perhaps indicates that he died in the Siege, but Upton does not say either way.

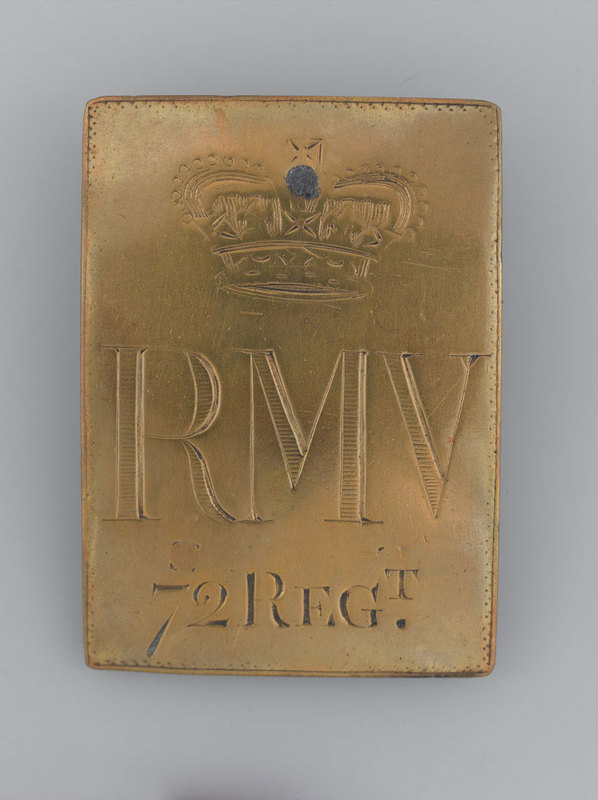

Catharine Upton is also unknown in that, despite her two published works, she lacks a portrait. It is not known what she looked like. Unlike the powerful military men mentioned in her “Account” like the Governor of Gibraltar, she does not have known surviving portraits. She leaves a visual hole in the record, like many men and women of her day. Still, to satisfy this need, an artifact or depiction showing her connection to the Siege and the military can stand in. After all, the Siege looms large in the records of her life: in the magazine reprints of her account of the Siege and her own prefaces to her published works. Two sorts of visual representation for Upton can be found in the 1784 painting of the Siege and the shoulder plate from the uniform of the 72nd Manchester Regiment. The painting shows a female onlooker lurking at the very edge of the painting, watching the military drama. Though the painting depicts an event that took place after Upton had left Gibraltar, the woman’s behavior makes her quite similar to Upton: both are woman existing in a predominantly male and military space, and both are acting as eye-witness observers to events. The uniform part is a more direct connection—it is an insignia of the 72nd Regiment of Foot (Royal Manchester Volunteers), the regiment that her husband was a Lieutenant for.

Though these pamphlets and visual “stand-ins” offer interesting glimpses into Upton’s life and role in society, they serve as a reminder that the story is not really about her. Instead, it is about the things around her—her husband, her children, the Siege. Even when her “Account” was reprinted in the magazines, the three magazines left out her name and simply referred to her as a “lady present on the spot”. They do not really give her the attention she is due. Despite publishing the two pamphlets under her own name, she exists at the edge of the records, lingering at the sides or background of a larger scene. As with the Hanoverian soldiers presented earlier, the unknown woman is a part of the narrative without being the focus, placed into the background or the periphery to support other events or characters. The same visual effect is employed in the two paintings—just as the Hanoverians are small figures in the background, the one visible woman in the scene in the 1784 painting is placed out of prominence in the background. In this way, Upton exists in history—both seen and unseen, straddling the line between uncommonly famous and commonly obscure.

Word Count: 1230

Bibliography:

"Account of the Siege of Gibraltar”. The Scots Magazine 43, (September 1781): 478-481. http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/6263412?accountid=11311.

Creswell, Samuel Frances. Collections towards the History of Printing in Nottinghamshire. London: 1863.

Hurl-Eamon, Jennine. Marriage and the British Army in the Long Eighteenth Century: 'The Girl I Left Behind Me'. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199681006.001.0001.

Upton, Catharine. “Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse, by Mrs. Upton, Authoress of the Siege of Gibraltar, and Governess of the Ladies Academy, no. 43 Bartholomew Close”. London: 1784.

---- “The siege of Gibraltar, from the twelfth of April to the twenty seventh of May, 1781. To which is prefixed, some account of the blockade.” London, 1781.

[1] "Upton, Catherine," Romantic Circles: A refereed scholarly Website devoted to the study of Romantic-period literature and culture, accessed April 20, 2017, http://www.rc.umd.edu/person/upton-catherine.

[2] Catharine Upton, “Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse, by Mrs. Upton, Authoress of the Siege of Gibraltar, and Governess of the Ladies Academy, no. 43 Bartholomew Close”, (London: 1784), iii.

[3] Jennine Hurl-Eamon, Marriage and the British Army in the Long Eighteenth Century: 'The Girl I Left Behind Me' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199681006.001.0001, 35.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Account of the Siege of Gibraltar”, The Scots Magazine 43, (September 1781): 478, 479, 480, http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/6263412?accountid=11311.

[6] Samuel Frances Creswell, Collections towards the History of Printing in Nottinghamshire, (London: 1863), 36.

[9] Catharine Upton, “The siege of Gibraltar, from the twelfth of April to the twenty-seventh of May, 1781. To which is prefixed, some account of the blockade,” (London, 1781), vii.