Place: Civic Pride and Cosmopolitanism

Visitors to Bristol, England, in the middle of the 18th century would have been impressed by the city’s booming trade economy and urban landscape. A “second-tier” English seaport city like Norwich, Liverpool, and Glasgow, Bristol’s growth and development during this period driven by its expanding access to Atlantic trade.[1] Bristol merchants’ primary cargos were sugar and slaves; their main points of contact were Africa, the West Indies, and North America. In the early part of the century, Bristol was outcompeted by other seaports: though the largest British port in 1700, its control of the slave trade was overtaken by Liverpool in the 1730s, and its control of the tobacco trade was lost to Glasgow by the 1740s.[2] But despite this relative decline, Bristol continued to thrive, its population rising from 45,000 around 1750 to 64,000 in 1800.[3] Late in the century, outbreak of rebellion in Britain’s North American colonies would threaten bankruptcy for Bristol’s trading houses, but they would adapt and ultimately become stronger than ever by establishing government war contracts, turning increasingly to smuggling and privateering, and expanding their global scope to include ports outside the British empire’s mercantile system.[4] A midcentury visitor to Bristol might not have been able to predict the coming civil war, but a tour of the city would have demonstrated its commercial potential: in the 1750s and 60s, Bristol’s economy was on the rise, and at its heart were international trade, a growing sense of cosmopolitanism, and civic pride.

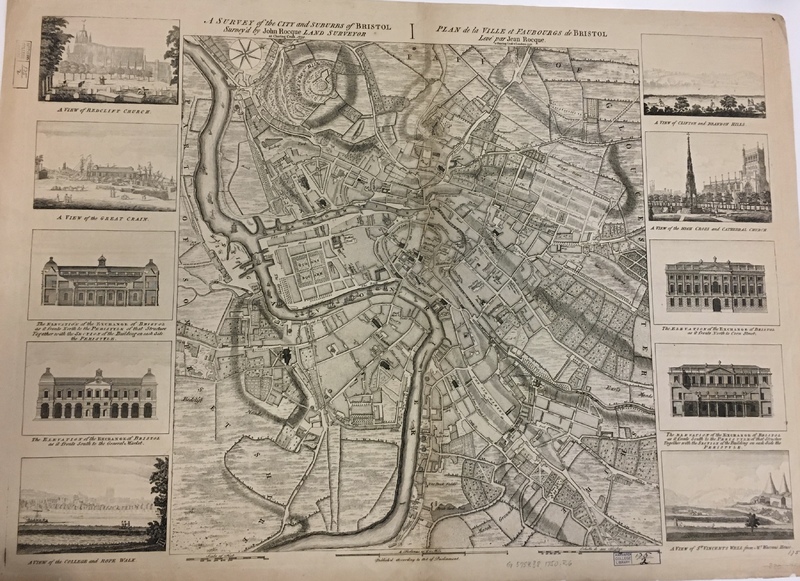

In 1750, surveyor John Rocque published a map, “A Survey of the City and Suburbs of Bristol,” that today tells us much of what contemporary visitors might have encountered in the city.[6] Indeed, visitors would have appreciated the map’s detail and clarity, perhaps staying in its Greyhound Inn or worshipping inside one of the many churches it depicted. The map provides a sense of Bristol’s urban atmosphere, complete with multiple alms houses, designated open spaces, a customs house, a grammar school, and a mint. Street names like Carolina Court and Jamaica Street hint at the cosmopolitan culture global trade brought to the city. The Avon River defines the town’s geography, and Rocque orients the map to foreground the river’s upward flow through the city center. The river, of course, was the lifeblood of the trade in Bristol—aside from providing a sense for the city’s landscape, Rocque’s map underlines contemporary awareness of just how fundamental trade was to Bristol’s identity.

In addition to its global connections, Bristol was embedded in commercial networks at home, and both domestic and international ties seem to have figured prominently in everyday life. The Avon as it appears in Rocque’s map is choked with ships of many sizes passing through the city and clustered at its heart, driving the commercial economy with cargo from places near and far. Transatlantic traffic must have been fairly constant: in 1766, an ad appeared in a London newspaper seeking contact with the crew or captain of the Jolly Princess, a ship that had returned to Bristol from Barbados four years previously.[7] The presence of this ad hints at the regular flow of goods, people, and ideas between Bristol and the Caribbean islands, as well as their dissemination across England from the Bristol nexus. Though Rocque’s map makes no explicit allusion to global trade, it points to dense domestic networks by including the direction of the Avon’s current, an important detail for understanding movement through the city, and arrows directing the map’s users toward adjacent towns. An ad in the December 6, 1766 edition of the London Evening Post tied Bristol’s national and international networks together by selling exotic American Pine-Bud tea to readers in Bristol, Piccadilly, Bath, York, Sheffield, and Oxford, noting that the tea should be sweetened with sugar, presumably imported from America.[8] Though these documents cannot provide broad data about trade and commerce in mid-18th century Bristol, the casual nature with which they connect the city to places as disparate as Barbados and Sheffield centrally locates Bristol amid a trade network both expansive and dense.

John Rocque’s map, for which Rocque likely took into account the views and self-image of Bristol’s mercantile elite, reveals contemporary awareness of and pride in the importance of trade to civic identity. The map’s border comprises ten prints, six of which show attractive “views” of Bristol, including the “Great Crain,” a tool for moving goods on and off the many ships docked on the Avon. The remaining four prints are all “elevations” of the Exchange of Bristol, the city’s main trade hub, which remove the Exchange from its urban environment to draw the viewer’s attention to its impressive architecture. The detailed renderings and the captions’ descriptions of the streets from which one could see each side of the Exchange indicate the importance of this building in the mind of the mapmaker. Indeed, Kenneth Morgan explains that when the large new Exchange was built in the middle of the century, it symbolized the important connections between trade, wealth, political power, and civic pride in Bristol.[9] The elevations on the border of Rocque’s map boast of the trading industry flourishing at the foundation of Bristol’s prosperity.

Rocque’s map carries the voice of the mercantile elite more than the people filling Bristol’s alms houses, but these were the people who would have the loudest political voices when war broke out with Britain’s North American colonies two and a half decades after the map was published. The nonimportation policies of the Continental Congress were sure to disrupt life in Bristol, so they likely opposed any move by Parliament that would prolong the conflict. As it stood in 1750, at least from the point of view of John Rocque and those who urged him to print four separate images of the Exchange, Bristol stood proudly at the center of a large trade network, primed for whatever opportunities for more growth the future would bring.

Word count: 1029

[1] Mark A. Peterson, "The War in the Cities," in The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution, ed. Jane Kamensky and Edward G. Gray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 199.

[2] Kenneth Morgan, "Building British Atlantic Port Cities: Bristol and Liverpool in the Eighteenth Century," in Building the British Atlantic World, ed. Daniel Maudlin and Bernard L. Herman, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 213.

[3] B. R. Mitchell, International Historical Statistics: Europe, 1750-2005, 6th ed. (New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

[4] Mark A. Peterson, "The War in the Cities," in The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution, ed. by Jane Kamensky and Edward G. Gray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 200.

[5] Kenneth Morgan, "Building British Atlantic Port Cities: Bristol and Liverpool in the Eighteenth Century," in Building the British Atlantic World, ed. Daniel Maudlin and Bernard L. Herman, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 213.

[6] Rocque, John. A Survey of the City and Suburbs of Bristol. Harvard Map Collection Digital Maps. England. Bristol. Charing Cross i.e. London: John Rocque, Published According to Act of Parliament, 1750.

[7] Public Advertiser (London, England), Tuesday, January 28, 1766; Issue 9748. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers.

[8] London Evening Post (London, England), December 6, 1766 - December 9, 1766; Issue 6101. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers.

[9] Kenneth Morgan, "Building British Atlantic Port Cities: Bristol and Liverpool in the Eighteenth Century," in Building the British Atlantic World, ed. Daniel Maudlin and Bernard L. Herman, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 218.