New Bern: A Focal Point of Foreign and Domestic Discourse

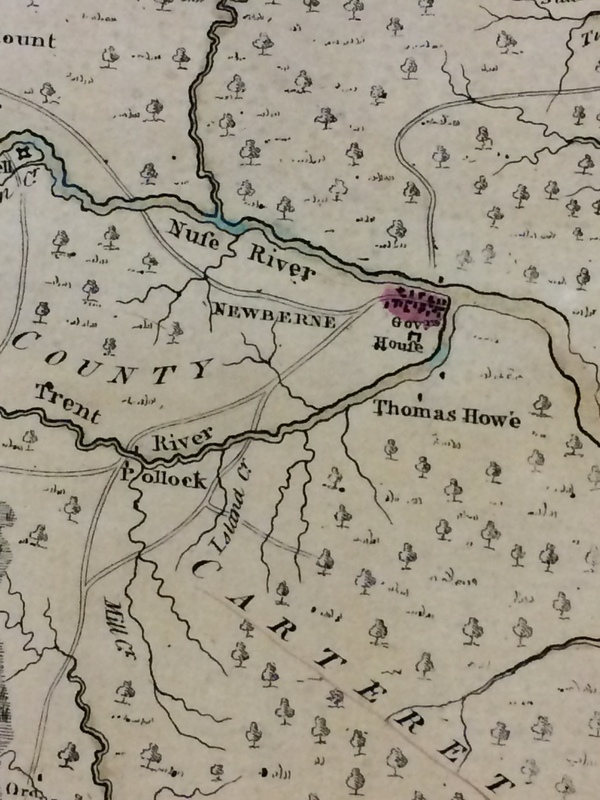

Located on the confluence of the Trent and Neuse Rivers along the Atlantic Coast, New Bern, North Carolina, the capital of the North Carolinian colonial government, formed the center of domestic and foreign political discourse. Both the opening articles speech printed in the New Bern-based North Carolina Gazette, and a close-up of New Bern on John Collet’s 1770 “complete map of North Carolina,” suggest that New Bern served as North Carolina’s most vibrant and politically engaged city. The city’s river access enabled it to communicate fairly easily with major domestic cities and the British Crown and Parliament, and publish authors both critical of and sympathetic to American grievances in the lead-up to the Revolution.

The first two pages of the March 27, 1775 North Carolina Gazette—which most legibly includes a speech delivered by Mr. Cruger to the Assembly on American Affairs—suggest New Bern was a center of political discourse immediately preceding and during the American Revolution. Published in New Bern, the North Carolina Gazette’s sub-header reads “with the latest advices, foreign and domestic.” The Gazette’s sub-sub header reads, in Latin, “semper pro libertate et bono publico,” or “always for freedom and the public good.” This implies the Gazette covered both domestic and international political affairs, targeted an educated and politically engaged reader-base, and served colonists and British citizens of a variety of political leanings.

The first article to appear on the Gazette’s cover page is a “Summary View of the Rights of British America,” addressed to the King from an anonymous author referred to as “Tribunus.” Although much of this first article is illegible, Tribunus describes himself as British subject, but articulates that increased British taxation and regulation rightly engendered discourse in the colonies surrounding both natural rights of men and the “fair constitutional rights” guaranteed to every free British citizen. He writes that the “proceeding against our Brethren in America” is in “open violation of the unnatural laws of Equity and Justice.” Tribunus is qualifiedly sympathetic to coalescing American revolutionary sentiment, but clearly sees himself as a British subject and attempts to convince the British government to reverse its course. His reference to “Brethren in America” suggests he wrote his article from the British Isles, rather than in North Carolina, which means the Gazette would necessarily have acquired his discourse from abroad. This implies that the newspaper and the colonial government in New Bern were in consistent contact with Britain.

The second article, a speech delivered by Mr. Cruger to the Assembly on American Affairs, highlights a different, albeit also British perspective on growing unrest in the to-be rebellious colonies. Although this Gazette was published and distributed on March 27, 1775, Mr. Cruger delivered the speech on December 16, 1774. Although the article never explicitly references where the Assembly on American Affairs was located, this gap suggests it formed part of the British government in London, corroborating the Gazette’s claim to publishing both foreign and domestic advices. Mr. Cruger frames his argument differently from Tribunus, writing that “Britons ought to view [American subjects’ acts of Imprudence] with an Eye of Tenderness, hurried not (as has been unkindly said) by a rebellious spirit, but by that generous Spirit of Freedom.” Although Cruger perceives the American colonies similarly to Tribunus, he advises less assertive action.

A close-up of New Bern on John Collet’s “complete map of North Carolina” also suggests the city was situated at an easy access point to the Atlantic, which would have facilitated communication with Britain and other domestic cities. The city sits at the meeting point of the Nuse and Trent Rivers, one of the only cities along those two rivers and near the state’s northern Atlantic coast. The map at large is commissioned “for his majesty George III,” emphasizing ties between North Carolina and its New Bern-based colonial government and the “mother country.” New Bern is one of several depicted cities in a map that largely emphasizes state topography. The physical location of New Bern confirms the dual foreign and domestic content of The North Carolina Gazette. Notably, the third printed article in the Gazette is a series of commercial mandates issued by the Pennsylvania Convention in Philadelphia, implying trade and communication between New Bern, Philadelphia, and Britain, at the very least. These routes certainly carried more than material goods. The contentious political and intellectual discourse printed in the 1775 Gazette offers but a glimpse at the exchange of ideas New Bern was likely at the center in Revolutionary America.

Word Count: 746