Joseph Galloway -- The Occupation of Philadelphia

Omeka Three: Joseph Galloway

Zachary Gardner

Joseph Galloway, like Peter Oliver and William Franklin, was a lawyer, intellectual and loyalist. During British occupation of Philadelphia, Galloway assisted the British war effort in countless ways. He held a variety of administrative positions, recruited men for the army, and led raids into the countryside for cloth and forage. Additionally, as the highest civilian leader in Philadelphia and leader of the local loyalists, Galloway spoke for the experiences of the local inhabitants and voiced their concerns about British occupation. Specifically, Galloway revealed that many loyalists felt unprotected and mistreated under British rule. He uncovered their precarious position, whereby, according to Galloway, loyalists wanted to assist in operations of the British army, but feared patriot reprisal and depredation without any assurances of British protection. The real and valid Loyalist concerns, which Galloway raised, undermine General Howe’s facile understanding of loyalist behavior – “Alas, [loyalists] prate & profess much; but when you call upon them they will do nothing.”[1] Galloway and his story serve as evidence that the situation in Philadelphia was far more complicated.

Raised in an affluent family in Maryland, Galloway was a precocious child, perhaps even a prodigy. He quickly took to law, passed the bar in 1747, and opened a practice in Philadelphia at the age of 16.[2] As a lawyer, Galloway earned renown as an authority on land and property titles. According to advertisements, he regularly served as the executor to many estates – a post which led to great personal enrichment.[3] Beyond law, Galloway was a voracious reader and autodidact;[4] he was fluent in the classical tests, fascinated by the sciences, and dedicated to higher learning. A pamphlet reveals that he even served as the elected president of the American Philosophical Society for nearly a decade.[5] In 1756, Galloway turned to politics and was elected to the Provincial Assembly of Pennsylvania, serving as a representative, and later Speaker, until 1775.[6]

When the issue of independence arose, Galloway became a fierce and committed loyalist. Unlike most colonists whose political motivations were likely pragmatic or prosaic,[7] Galloway was a doctrinaire, driven by his faith in monarchism. Simply put, Galloway believed that a monarchy best affirmed the rights of men, and ensured the protection of property.[8] In 1775, he submitted before the First Continental Congress a proposal, later called the Galloway plan, which expanded upon Benjamin Franklin’s Albany plan of 1754 and outlined a path to reconciliation with the British. Specifically, the Galloway plan suggested that the British Parliament sanction a unicameral American parliament, a third house, which would serve, in peacetime only, under the king and alongside the British parliament.[9]

Importantly, Galloway was a member of a learned, hermetic aristocracy.[10] He held membership in a Gentleman’s club on the Schuylkill River which gathered the area’s most influential men for hunting and fishing.[11] He was privileged, erudite, supercilious, and fearful of mob rule. In fact, Galloway thought the patriots were benighted fools, calling them “licentious”, emotive, “governed only by the barbaric rule of frantic folly.”[12] In contrast, Galloway espoused his own level-headedness. Throughout his polemic, “A Candid Examination”, he repeatedly emphasized a sense of judiciousness, relying upon phrases like “calm reason”, “candid examination”, “reflection” and “cool and dispassionate argument.”[13] Moreover, he purported that the question of independence must remain in the hands of those capable of reason – that is, he suggested, “men of property”, “men of influence”, “men of consequence.”[14]

After the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777, Galloway became the leading civil authority in Philadelphia. He held a strong relationship with General Howe, testifying that he “frequently dined with [him]… and lived [just] next door.”[15] Appointed Superintendent of the Police and Port in 1777,[16] Galloway dutifully served the British in all capacities. In fact, his contributions to the British cause within Philadelphia and Germantown were nearly ubiquitous; he “assiduously”[17] procured information on the state of the Middle Colonies – intelligence that General Cornwallis deemed, “very material.”[18] In addition, Galloway managed exports and imports, keeping accounts with all venders of rum, salt, molasses and medicines,[19] recorded the names of inhabitants who had pledged oaths of allegiance to the crown, and oversaw the victualing of the royal army, “procuring blanketts for the troops who had lost their own in the Battle of German town.”[20] Incredibly, and to the British engineers’ incredulity, Galloway even erected a damn on the Blakely and Province islands in just six days, allowing the army to erect batteries against Mud Island fort.[21] “[Galloway] was applied to and consulted on business in almost all the general and different departments of the army”, wrote Scots magazine, “procur[ing] guides and horses for the troops and magazines of forage.”[22]

In addition to logistics, Galloway assisted the British war effort by enlisting and leading local loyalists. He raised a troop of soldiers from the local population and engendered the support of eighty volunteers to serve administratively without remuneration.[23] Moreover, his unstinted commitment to the royal cause extended to military leadership. To seize sparse cloth, Galloway conducted raids, in both daylight and darkness, throughout Germantown and Buck’s county. These raids were often bloody engagements, as both armies struggled to gather provisions.[24] During one raid, Galloway and his volunteer force inflicted eight casualties upon the enemy outside Germantown and took a major and several officers as prisoners.[25]

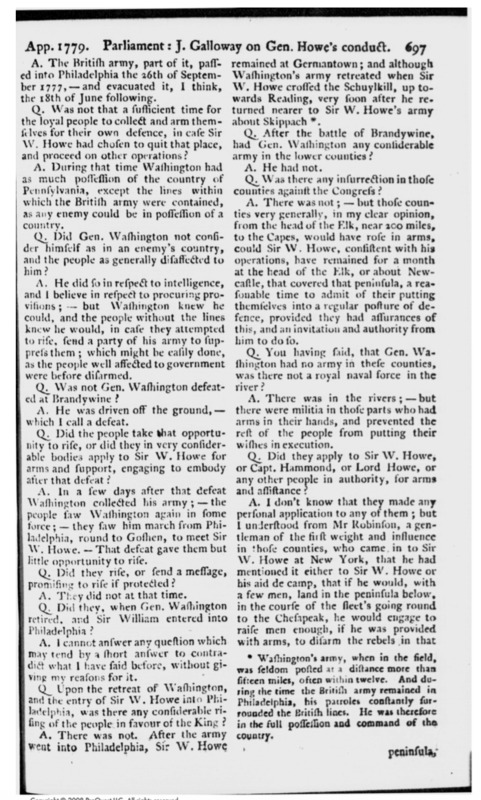

Despite his loyal service to the crown, Galloway was also highly critical of the British. A tacit spokesperson for loyalists, Joseph Galloway voiced their concerns, which bespoke serious British miscalculations -- blunders which likely cost General Howe the loyalist support he had anticipated. As a perverse application of rule, Galloway criticized Howe’s use of martial law, which he believed alienated British supporters. In a letter to General Germain, Galloway wrote that “numerous inhabitants who remained [in Philadelphia], almost unanimously concur’d in their applications to me to know whether they were to be governed by military Law or restored to their Civil Rights.”[26] British reliance on martial law, which truncated peacetime liberties, made loyalists insecure about their wartime status and resentful of the “double standard that treated them as inferiors to redcoats.”[27] Particularly, martial law compelled loyalists to feel like tools of war rather than British subjects worthy of protection and support. Instead of reaffirming and invigorating loyalist faith in British rule, martial law weakened it. According to Galloway, civil law, on the other hand, provided “general satisfaction, because it esteemed a prelude to their being soon restored to the Enjoyment of Civil Liberty, and a Settled Constitution between the two Countries.”[28] Galloway implies that the loyalists in Philadelphia living under martial law felt mistreated by British soldiers and unsure of future protections.

Additionally, Galloway believed that the British government had not sufficiently requested nor supported the loyalist citizens for them to independently go to war. To General Germain, Galloway testified that “many [loyalists] came into the [British] camp, but returned again to their habitations.”[29] Galloway continued, “I do not know of any that joined in arms, -- not one; -- nor was there any invitation for that purpose. – By Sir W. Howe’s declaration … he only requested the people to stay home.”[30] Galloway clarifies that General Howe did not even request loyalist assistance. In fact, General Howe, according to Galloway, instructed loyalists to return to their homes, sanctimoniously considering them “military amateurs adverse to discipline and cowardly in combat.”[31] Through these comments, Galloway insinuates that Howe’s grumbles about loyalist participation were in essence a retroactive complaint to save face after British defeat.

Furthermore, Galloway explained that, even if General Howe had requested loyalist support, the British army did not provide the loyalists with sufficient safeguards to justify risking their property, their families, and their lives. “It is not natural”, conferred Galloway, “that [loyalists,] people of property, will join an army passing from Philadelphia, leave their wives and families, and their property, liable to be destroyed every moment after the departure of the army, without some assurance, -- or assurances that the army would continue with them, or be ready to protect them.”[32] For example, Galloway pointed to the loyalists in New Jersey who, after assisting the British at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton, were forced to flee to New York as the British army moved onward.[33] These men, Galloway said, were fiercely beaten, their homes depredated and their shops pillaged. It would be unfair to expect the loyalists in Philadelphia to assume the same risks with such few assurances.

In sum, Joseph Galloway was an exceptional figure and leader in both peacetime and war. As a member of Congress, Galloway worked tirelessly to stave off independence, under the belief that there could be no safety or liberty in a democracy.[34] The thought of independence as a panacea to American troubles stood repugnant to him. Once war was declared, however, Galloway assiduously served the British war effort in the hope of reestablishing British rule. He took control of the military logistics and even led raids throughout Germantown and its purlieu. But perhaps most interestingly, Galloway voiced the concerns of the many decent and sedulous loyalists caught in abeyance: on the one hand, fearful of the mutinous patriots, but also neglected and mistreated under British occupation. He reaffirmed that the American Revolutionary War was not a fight of good against bad, of right against wrong, or of liberty against tyranny. Instead, the war upended the existing social order to an unexpected magnitude. It encompassed all in a prolonged, and depraved struggle, in which prior convictions were often disregarded for basic survival needs.

Words: 1523

[1] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions, (New York: W.W Norton Company, 2010), 224.

[2] Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[3] Advertisement, The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) 12/1/1764

[4] Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[5] Election Returns, The Pennsylvania Journal (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) 1/11/1775

[6] Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[7] Generally, most colonists’ political motivations were pragmatic – driven by the accumulation of material wealth – or prosaic – spurred by the need for basic staples, such as food, shelter, medicine and clothing etc. Galloway, however, was motivated by lofty principles of government.

[8] Joseph Galloway, Plan of Union, (9/28/1774)

[9] Joseph Galloway, Plan of Union, (9/28/1774)

Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[10] Again like Peter Oliver

[11] Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[12] Joseph Galloway, “A Candid Examination” Printed by James Rivington MDCCLXXV (New York)

[13] Joseph Galloway, “A Candid Examination” Printed by James Rivington MDCCLXXV (New York)

[14] Joseph Galloway, “A Candid Examination” Printed by James Rivington MDCCLXXV (New York)

Joseph Galloway, Plan of Union, (9/28/1774)

[15] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[16] Frank Baker, “Joseph Galloway” American National Biography Online, (London: Oxford University Press, 2000)

[17] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[18] Testimony of the Earl of Cornwallis Feb 13, 1784 Loyalist Transcripts XLIX

[19] Loyalist Transcripts, L, 514 (Accessed through: John M. Coleman, “Joseph Galloway and the British Occupation of Philadelphia, “Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies Vol. 30, No. 3 (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1963)

[20] Loyalist Transcripts, L, 514 (Accessed through: John M. Coleman, “Joseph Galloway and the British Occupation of Philadelphia, “Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies Vol. 30, No. 3 (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1963)

[21] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

Testimony of John Montresor, Esq., late Chief Engineer, Fed 20, 1784.

[22] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[23] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[24] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions, (New York: W.W Norton Company, 2010), 235.

To be clear, Galloway was not integrated into the Army but rather led a group of volunteer loyalists, almost like a militia.

[25] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[26] Letters Galloway to Germain, March. 18, 1779 (Accessed through the 18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers)

[27] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions, (New York: W.W Norton Company, 2010), 225.

[28] Letters Galloway to Germain, March. 18, 1779 (Accessed through the 18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers)

[29] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[30] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[31] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions, (New York: W.W Norton Company, 2010), 225.

[32] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[33] Mr. J Galloway’s Examination, Scots magazine, Dec 1779; 41, British Periodicals

[34] Or perhaps to Galloway, a kakistocracy.