Charleston during the American Revolution

In an issue of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette from March 11th, 1768, there is a short obituary for a craftsmen named Alexander Petrie. The exact lines are as follows: “On Sunday last died here Mr. Alexander Petrie, Silver-Smith, who had acquired a handsome Fortune, with a fair Character, and had some Time ago retired from business.”[1] There is much to be intuited about Petrie from this short text, though perhaps the most telling is the quote’s location in the paper. The one-sentence farewell is the only death announcement in its section. It is sandwiched between two pieces of political news that are potentially quite important. The first is regarding a decision by a Georgie court regarding the bounty for a group of fugitive sailors.[2] The second is about a Monsignor from London originally headed to Nova Scotia, and his decision to remain in Charleston.[3] Petrie’s death is important enough for him to be remembered fondly in the middle of breaking news, perhaps because he played some sort of prominent role in Charleston before his death in 1768.

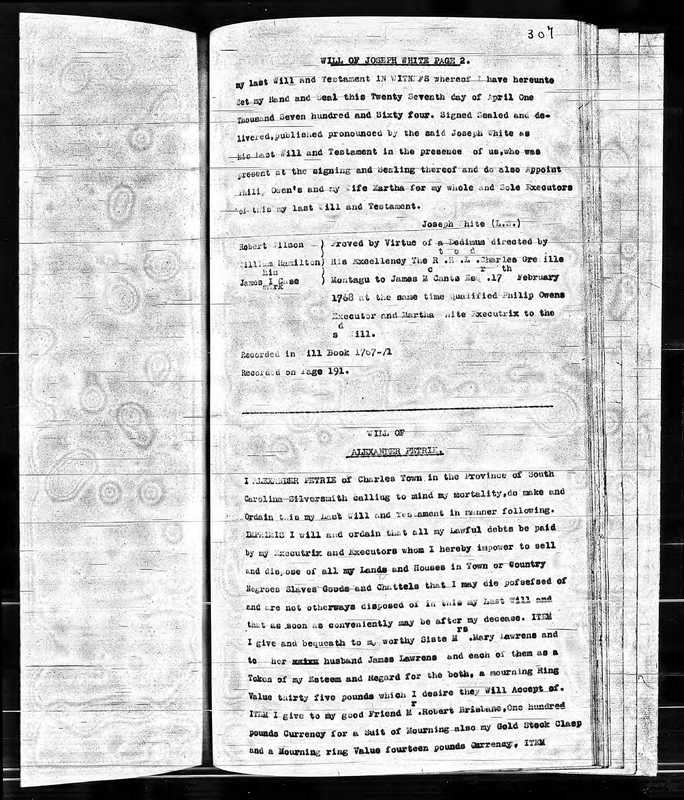

Though the obituary names Petrie as a Silver-Smith, there is little evidence of his work in other newspapers from South Carolina or from any other colonies. Searching his name on the American Historical Newspapers database yields only the newspaper announcing his passing and a newspaper dated years later publicizing the selling of his house.[4] There are no articles advertising his goods, and he also does not leave a silver shop or silver goods to his eldest son in his will. Upon his Father’s death, Edmund Petrie receives “a tract of 539 acres on Oakley Creek, Granville County and a town lot in Dorchester, SC.” Clearly then, Alexander Petrie did acquire the fortune discussed in his obituary, but the lack of information on his silver is suspicious. Perhaps it is simply that wealthy Charlestonians bought Petrie’s goods directly from his shop, so advertisements in the paper were of little use to him. This would fit with the idea that Charleston was a hugely wealthy city during this time period, and a place that artisans flocked to and flourished in. However, no other mention of Petrie’s silver raises the question about what other role he possibly could have played in South Carolina to establish himself.

Ancestry Library places Petrie’s birth in Moray, Scotland in 1707.[5] The database has no record on his exact arrival in the colonies, but his marriage license from 1748 is granted by South Carolina.[6] A secondary source suspects Petrie arrived in South Carolina in the 1740s[7], and his wedding proves he arrived before ‘48, which means his arrival lines up very well with the Jacobite uprisings. The uprisings, popular with Scotts, took place in the 18th century across Britain and involved five attempts to reinstate the former king displaced by the Glorious Revolution.[8] The final Jacobite rebellion began and then ended in failure in 1745, which resulted in Scotts who took part in the uprising being exiled to America by the British empire. The Ancestry Library database states that in 1745 “Scottish rebels were transported to America after a Jacobite attempt to put Stuarts back on the throne failed.”[9] If Petrie was one of these exiled rebels, that would explain both his timeline and lack of formal documentation upon his arrival in South Carolina. Or perhaps he was not formerly exiled, but chose to leave Scotland himself after the rebellion failed and follow those who were being expelled. Whether or not Petrie was an active participant in the rebellions, his arrival time in the colonies suggest he left Scotland, forced or not, with feelings of disdain towards England.

Petrie’s time of arrival as well as his Scottish heritage suggest he would have leaned towards patriotism, so it is worth noting and exploring the fact that he retired from being a Silver-Smith the year that British Parliament passed the Stamp Act. According to Petrie’s ancestry database, “[his] works were in silver and gold from coffee pots to simple spoons. He also made silver ornaments as jewelry to be used in trade and diplomatic overtures between colonists and native Indian tribes. He retired about 1765.”[10] Though it might just be a coincidence that Petrie retired the same year that Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the tax caused enough of a ripple in the colonies that the former might have affected the latter. The Stamp Act placed a tax on things like “legal papers, newspapers, pamphlets, cards, almanacs, and dice.”[11] Therefore, it did not directly affect Petrie’s silver, but it may have affected how he advertised and shipped his goods. Additionally, people might have been more interested in melting down silver to make money to pay for the new tax, than they were in purchasing decorative silver pieces like the ones Petrie made. Finally, there is also the chance that Petrie left his work because of his potential status as patriot. If Petrie was part of the Jacobite uprisings, he might have been inclined to join the rebellion in the colonies and leave behind his Silver-Smith business. In 1765 Petrie was already an old man most likely unable to join in any physical forms of protests, but the Stamp Act might have inspired him to express patriotism by other means. Either way, Petrie’s retirement coinciding with the Stamp Act suggests that rising patriotism in the colonies disrupted his Silver-Smith business.

Based on his obituary in the South Carolina and American General Gazette, Alexander Petrie was a prominent citizen in Charleston. The newspaper suggests Petrie acquired his fortune as a Silver-Smith, though there is little to be found on him selling his goods, and he did not leave anything silver related to his oldest son in his will, leading one to suspect he might have established himself in other ways as well. His arrival time in the American colonies points to the idea that he might have taken part in the Jacobite uprisings in Scotland, which would in turn cause him to lean towards patriotism upon his arrival in Charleston. Petrie retired from being a Silver-Smith the same year the Stamp Act was passed, suggesting that the beginnings of the war between Britain and its colonies disrupted his work, either because it became harder for him to sell his goods or because he joined the patriot cause. If Petrie did indeed participate in or support the Jacobite rebellions, one might be more inclined to believe it was the latter. All of the information collected in this profile suggests that Petrie most likely felt ties to patriotism and perhaps even took up the cause.

Bibliography

"Alexander Petrie." Ancestry Library. https://www-ancestrylibrary-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/family-tree/person/tree/23196323/person/5114511191/facts.

"Charleston, March 11." South-Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston, South Carolina), March 11, 1768.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Jacobite." Encyclopædia Britannica. February 09, 2007. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Jacobite-British-history.

"Migration to America in the 1700s." Ancestry Blog. https://blogs.ancestry.com/ancestry/2014/10/13/migration-to-america-in-the-1700s/.

"Mr. Petrie's Shop on the Bay by Brandy S. Culp from Antiques & Fine Art magazine." Mr. Petrie's Shop on the Bay by Brandy S. Culp from Antiques & Fine Art magazine. http://antiquesandfineart.com/articles/article.cfm?request=722.

Rose, John. "For Sale by Private Contract." South-Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston, South Carolina), August 12, 1771.

"Stamp Act." Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Stamp-Act-Great-Britain-1765.

[1] "Charleston, March 11," South-Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston, South Carolina), March 11, 1768.

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] John Rose, "For Sale by Private Contract," South-Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston, South Carolina), August 12, 1771.

[5] "Alexander Petrie," Ancestry Library.

[6] Ibid

[7] "Mr. Petrie's Shop on the Bay by Brandy S. Culp from Antiques & Fine Art magazine," Mr. Petrie's Shop on the Bay by Brandy S. Culp from Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

[8] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, "Jacobite," Encyclopædia Britannica, February 09, 2007.

[9] "Migration to America in the 1700s," Ancestry Blog.

[10] "Alexander Petrie," Ancestry Library.

[11] "Stamp Act," Encyclopædia Britannica, , https://www.britannica.com/event/Stamp-Act-Great-Britain-1765.

Word count: 1098