Charleston, South Carolina during the American Revolution

http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/4ec35e84cb0bc4e12e9c8961e4bb81d9.pdf

http://dighist.fas.harvard.edu/courses/2017/hist1002/files/original/4ec35e84cb0bc4e12e9c8961e4bb81d9.pdf Charleston, South Carolina, though not so commonly mentioned as cities like Lexington and Philadelphia, played an important role during the American Revolutionary War. Based on two primary sources, a map intended for a government council of the Province of South Carolina and a decree from a British official addressed to the people of Charleston, it seems England valued the city both for its real-estate potential and its balance of Tories and Patriots.

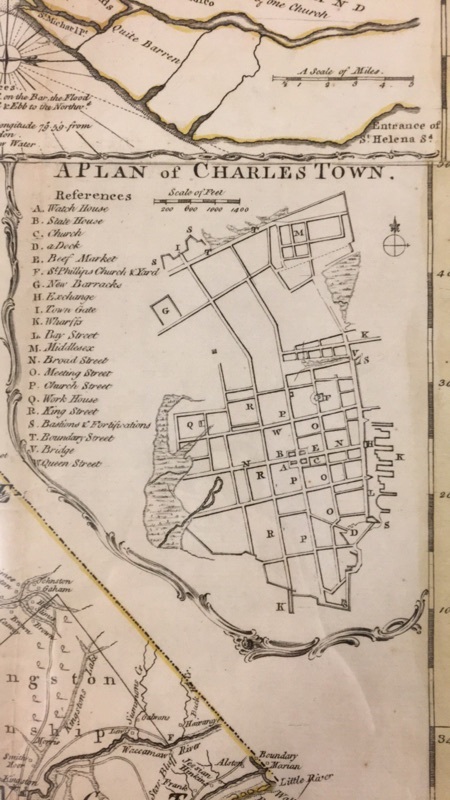

A map of South Caroline made by James Cook in 1773 for members of “the Honorable Commons House of Assembly of the Province”[1] illustrates the territory’s geographic location in the colonies. To the North is North Carolina. Georgia is at the Southwest border and “Cherokee land”[2] lies to the Northwest. The eastern end of the province borders the Atlantic Ocean, though the map focuses much more on land geography than it does the ocean or any bay, suggesting that South Carolina’s importance did not have to do so much with trade by ship. Instead, the map includes zoomed-in layouts of major cities such as Charleston. This sub-map is so detailed, it includes the location of specific buildings, such as the Watch House, the Church, and the State House.[3] The specificity with which Charleston is represented suggests that Charleston was an established city as well as an important hub. According to the map, the most important part about South Carolina was its people, particularly those in Charleston, rather than its natural resources. It is also worth noting that Cook’s map includes plans for two other cities, Georgetown and Camden. These plans include boxes designated to hold the same types of establishments as exist in Charleston. Therefore in 1773, government officials, presumably who were aligned with the British crown, were interested in the specific layout of the major city Charleston and intended to expand South Carolina with at least two more cities. England saw the city of Charleston as an important center of life in the colonies and saw the Province of South Carolina as having the potential to house even more metropolitan sites.

A proclamation from “Sir Henry Clinton, Knight of the Bath, General of His Majesty’s Forces, and Mariot Arbuthnot, Esquire, Vice-Admiral of the Blue”[4] suggests that Charleston was home to a significant population of both Patriots and Tories.[5] The proclamation urges those colonists who oppose English rule to reevaluate their decisions and realign themselves with the crown. Clinton writes to the Patriots of Charleston,

…to such of his deluded Subjects, as have been perverted from their Duty by the Factious Arts of self-interested and ambitious --, That they will still be received with Mercy and forgiveness, if they immediately return their Allegiance, and a due obedience to those laws and that Government which they formerly boasted was their best Birthright and noblest Inheritance, and a upon a due Experience of the Sincerity of their Professions, a full and free Pardon will be granted for the treasonable Offences which they have heretofore committed, in such a Manner and Form as his Majesty’s Commission doth direct.[6]

It is clear that Charleston must have been an important political hub in the colonies, as the King chose to address the citizens of this territory directly. Additionally, the people of Charleston were influential enough to warrant a formal attempt at turning them over to the British side. Perhaps the most notable part of this document, however, is a sentence at the end in which Clinton urges the Tory population to attempt to convert their ignorant brethren. “And we do hereby call upon all his Majesty’s faithful subjects to be aiding with their Endeavors in order that a Measure, so conducive to their own Happiness, and the Welfare and Prosperity of the Province, may be the more speedily and easily attained.”[7] Charleston most likely had a fairly equal population of Patriots and Tories, as England asked both the traitors to reevaluate their actions and asked the loyalists to push the traitors in the right direction. It is perhaps this mix of political ideas that made Charleston such an important part of the Revolution. England was interested in tipping a major colonial city that was sitting on the ideological edge, over onto its own side.

Charleston, South Carolina, a city often overlooked when talking about the American Revolution, played an important political role during the war nonetheless. Its geography and mix of Patriots and Tories made it valuable enough to Britain to have maps drawn up and formal decrees proclaimed.

Word Count: 747 (not including footnotes or works cited)

Bibliography

Cook, James. A Map of the Province of South Carolina. Scale not given. 1773.

Great Britain. Army. Proclamation. 1780 June 1. Early American Imprints, Series 1, no. 16790. Charles-Town: Printed by Robertson, Macdonald, and Cameron, in Broad-Street, the corner of Church-Street. Readex. http://infoweb.newsbank.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=Q63L55NSMTQ4NzI1NDg2Mi40OTU2NjU6MToxNDoxMjguMTAzLjE0OS41Mg&p_action=doc&p_queryname=3&p_docref=v2:0F2B1FCB879B099B@EAIX-0F30162D78BC2798@16790-@1 (accessed February 10th, 2017.

[1] Cook, James, A Map of the Province of South Carolina, Scale not given, 1773

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Great Britain. Army, Proclamation, 1780 June 1, Early American Imprints, Series 1, no. 16790, Charles-Town: Printed by Robertson, Macdonald, and Cameron, in Broad-Street, the corner of Church-Street, Readex

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid