Ukawsaw Gronniosaw's Narrative

How does one uncover the human experience of a West African native in the imperial British system? The task is not simple. The violent exploitation of the slave economy silenced many of the voices of the men and women from the Senegal region often by preventing them from becoming literate and excluding them from public life. When slave traders captured and sold people into slavery, they not only tore them from their home and forced them into an oppressive global labor system, but also took away their historical voice.

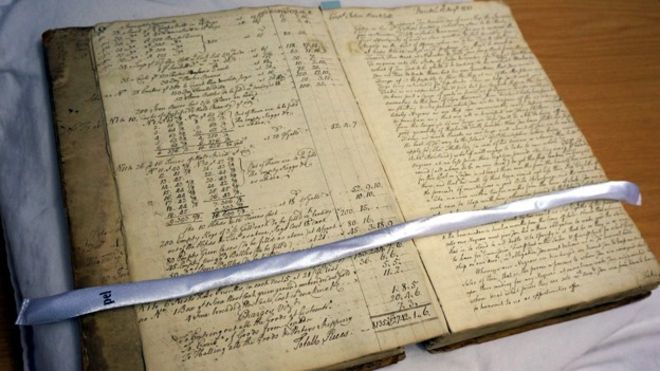

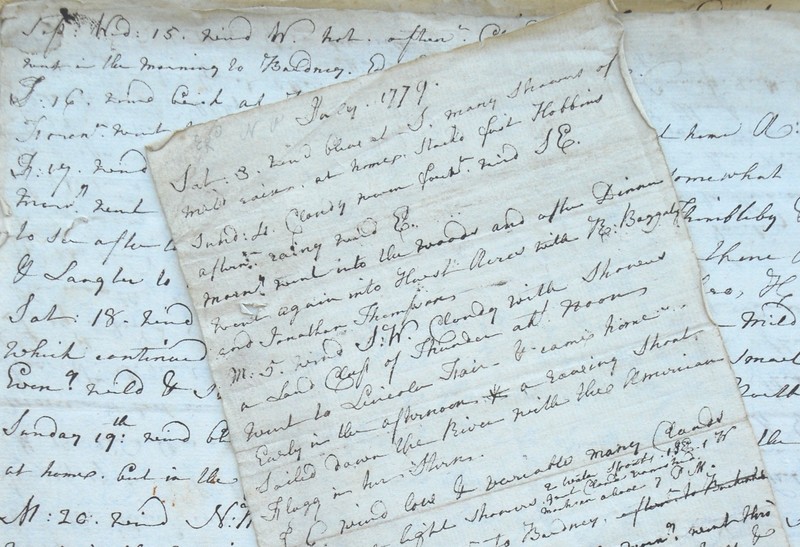

All of this makes it very difficult to find humanizing accounts of slaves and their lives. Slaves are instead documented in cold economic and descriptive terms, and can most easily be found in ships’ ledgers, estate records, and runaway slave advertisements. These records illuminate the brutality of slavery by reducing slaves to commoditized beings and ignoring their humanity.[1] One of the most famous examples of the dehumanization of slaves in the historical record is the diary of the Jamaican sugar planter, Thomas Thistlewood. His writings give a rare glimpse into life in a slave society in the 18th century from the perspective of the white master, and the commonplaceness of physical and sexual violence within it. While he recounts the names of his slaves and his interactions with them, his slaves function only as units of labor and objects upon which he exerts his authority as master through flogging, sadism, and rape.[2] Most of the written documents from the British imperial world treat West Africans as mere commodities and make it difficult for historians to extract the human story of slavery.

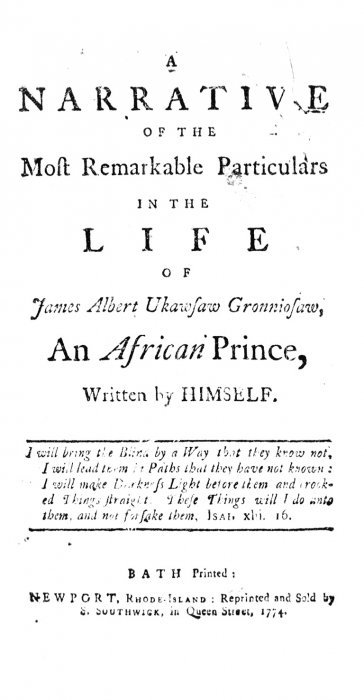

The slave narrative, however, writes against the commodified narrative of enslaved persons and can give historians a glimpse into the life and thoughts of people who endured slavery. The first of these published narratives appeared on the eve of the American Revolution in 1772, and told the story of a freed slave, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw.[3] In this autobiographical text, Gronniosaw gives his account of being captured in Senegal and sold into slavery, and tells his story in a way that millions of slaves only recorded on ships’ logs and in estate records cannot.

Gronniosaw’s autobiography tells a strange story that contradicts many of the later abolitionist slave narratives such as Oluadah Equiano’s (1789) and Frederick Douglass’s (1845). He does not rile against the evils of slavery and its horrors, but rather describes the experience as benign and uneventful – it is Gronniosaw’s life after he is freed that causes him the most trouble and heartbreak. In this unlikely story we can uncover details about one man’s experience with slavery in the British Empire in the 1700s and try to get a glimpse of the larger picture.

The narrative begins with Gronniosaw’s youth in the West African city of Bornou, where he describes his early years as being characterized by unease and melancholy. When a Gold Coast merchant promises to show him the world and then return him home safely, Gronniosaw’s parents agree to send him away. After taking him away, the merchant reveals that Gronniosaw “should not go home, but be sold for a slave,”[4] and eventually sells him to a Dutch Trader. The non-violent nature of the introduction of slavery in this text contradicts the common narrative of violent capture, but nevertheless reveals the trickery and bald-faced lying that would be used to extract humans from their homeland and force them into labor. Gronniosaw’s narrative also gives a picture of the structure of the slave trade in West Africa in the 18th century, in which there are merchants who work on the continent and then sell slaves to marine merchants who stop on the coast. The incipient moment of capture illustrates the actors and economic motivations of slave traders in the Senegal region.

The part of the Gronniosaw narrative in which he is enslaved provides a fascinating look at how the commodification of black bodies alters the dialogue on personal value. Gronniosaw is almost immediately concerned with his value on the human trafficking market, worrying that he was too small to be valuable to any master. Eventually, when he is purchased, he celebrates that the ship’s captain bought him “for two yards of check, which is of more value there, than in England.”[5] During his time as a slave, he recalls the kindness of his master and his desire to please him by becoming a literate and god-fearing man. This character appears to be a far cry from the curious and restless youth that was sold into slavery in Senegal. Suddenly, Gronniosaw celebrates subservience and derives personal value from being bought and sold by white masters.

After the death of Gronniosaw’s master and his family, this source of self-worth collapses and Gronniosaw’s most dire troubles begin. He experiences prejudice and discrimination while working on board a ship, struggles to find either a new master or steady employment, and lives on the brink of starvation. According to the narrative, the life of a newly freed black in the British Empire is not better than that of a slave. In fact, the loss of the care, protection, and value given by a master is the source of Gronniosaw’s greatest crisis. In many ways, this narrative tells the same story of commoditization, dehumanization, and struggle that is borne out by the economic records of slavery. However, the autobiography gives the story a human dimension and attempts to give a voice to the voiceless slaves that drove the British imperial system.

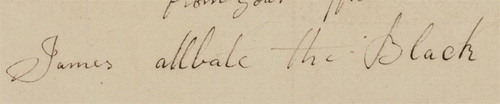

While Gronniosaw’s narrative provides a unique look into the life and thoughts of an enslaved person, we as historians must be careful not to extrapolate too far beyond the limits of the text. Frankly, the fact that his narrative exists and his story has been recorded sets him apart from the average slave, and therefore his experience is not entirely representative. Furthermore, Gronniosaw’s text, like any other was written for a specific purpose and with conscious goals. The white publisher, Walter Shirley, published a text designed to show the power of Christianity to reform the souls of African heathens, whom he describes as those “born… in Regions of the grossest Darkness and Ignorance.”[6] Gronniosaw, on the other hand, saw a more practical purpose for his autobiography, which was to make some money to support his life and family. The last several pages are devoted to economic difficulties that his family is facing and the strain that it is putting on him and his loved ones and the proceeds from the sale of the book were given directly to Gronniosaw himself.[7]

This text is convoluted because it serves many purposes, has been routed through a white author, and it is by definition an anomalous source. However, it is one of the only sources in the Revolutionary Era that allows us to peek into the life of a slave in a slave’s own words, and reveals in some ways the experience of a West African in the British Empire.

[1] Trevor Burnard, “Collecting and Accounting: Representing Slaves as Commodities in Jamaica, 1674-1784,” in Collecting Across Cultures ed. Daniela Bleichmar and Peter Mancall (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 191.

[2] Ibid, 178.

[3] Yuval Taylor, I Was Born a Slave (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 2.

[4] Gronniosaw Slave Narrative

[5] James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, An African Prince, As related by Himself (Bath: W. Gye, 1772), 6.

[6] Ibid, 12.

[7] Yuval Taylor, I Was Born a Slave (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 6.